Submitted by Carmyn de Jonge on Wed, 28/04/2021 - 11:14

Cambridge University researchers lead policy briefing on Nature-based Solutions for the climate and biodiversity crises

Written by Rogelio Luque-Lora

As societies face the triple challenge of enhancing human wellbeing, avoiding dangerous climate change, and protecting remaining biodiversity, increasingly there are calls to end siloed thinking and design solutions that simultaneously address each of these problems.

The expanding paradigm of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) is in line with these calls. According to Oxford-based NbS expert Nathalie Seddon and colleagues, NbS are ‘solutions to societal challenges that involve working with nature’. Examples include tree planting to sequester atmospheric carbon and restoring coastal habitats to mitigate floods.

A group of experts on NbS, specialising in the natural and social sciences and led by Cambridge University researchers Prof. David Coomes and Rogelio Luque-Lora, have just published a policy briefing outlining the underlying concepts of NbS as well a list of strategies and policy recommendations to take NbS to their full potential.

The briefing has been produced in association with the COP26 Universities Network, a growing group of UK-based universities and research institutes which include the University of Cambridge and Cambridge Zero. The paper is therefore oriented toward the United Nations Climate Change Conference which will be held in Glasgow later this year.

As explained by the authors, NbS can deliver both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation involves reducing the degree of climatic change (planting trees to absorb carbon dioxide is an example of this). Adaptation is about reducing communities’ exposure and vulnerability to the negative effects of climate change (for instance, flood protection). Moreover, by enhancing biodiversity, NbS can also boost the resilience of ecosystems to changing climatic conditions.

NbS often work by protecting existing ecosystems, which prevents the further release of carbon into the atmosphere and safeguards the biological diversity attached to those habitats. They can also work by restoring ecosystems which have previously been degraded, thereby improving the ability of these habitats to sequester carbon and host biodiversity. Both these strategies also have the potential to enhance the provision of ecosystem services, including water filtration and soil retention.

Other strategies include the sustainable management of working landscapes, such as agricultural land, and the creation of novel habitats. The latter of these strategies has also been referred to as ‘green engineering’ or ‘green infrastructure’, and can contribute to societal adaptation to climate change by cooling and cleaning the air in cities and providing physical and mental health benefits.

In the UK, NbS can support job creation and livelihoods, and can play a key role in ‘building back better’ after COVID-19 and can be more cost-effectively deployed than non-NbS approaches to mitigation and adaptation.

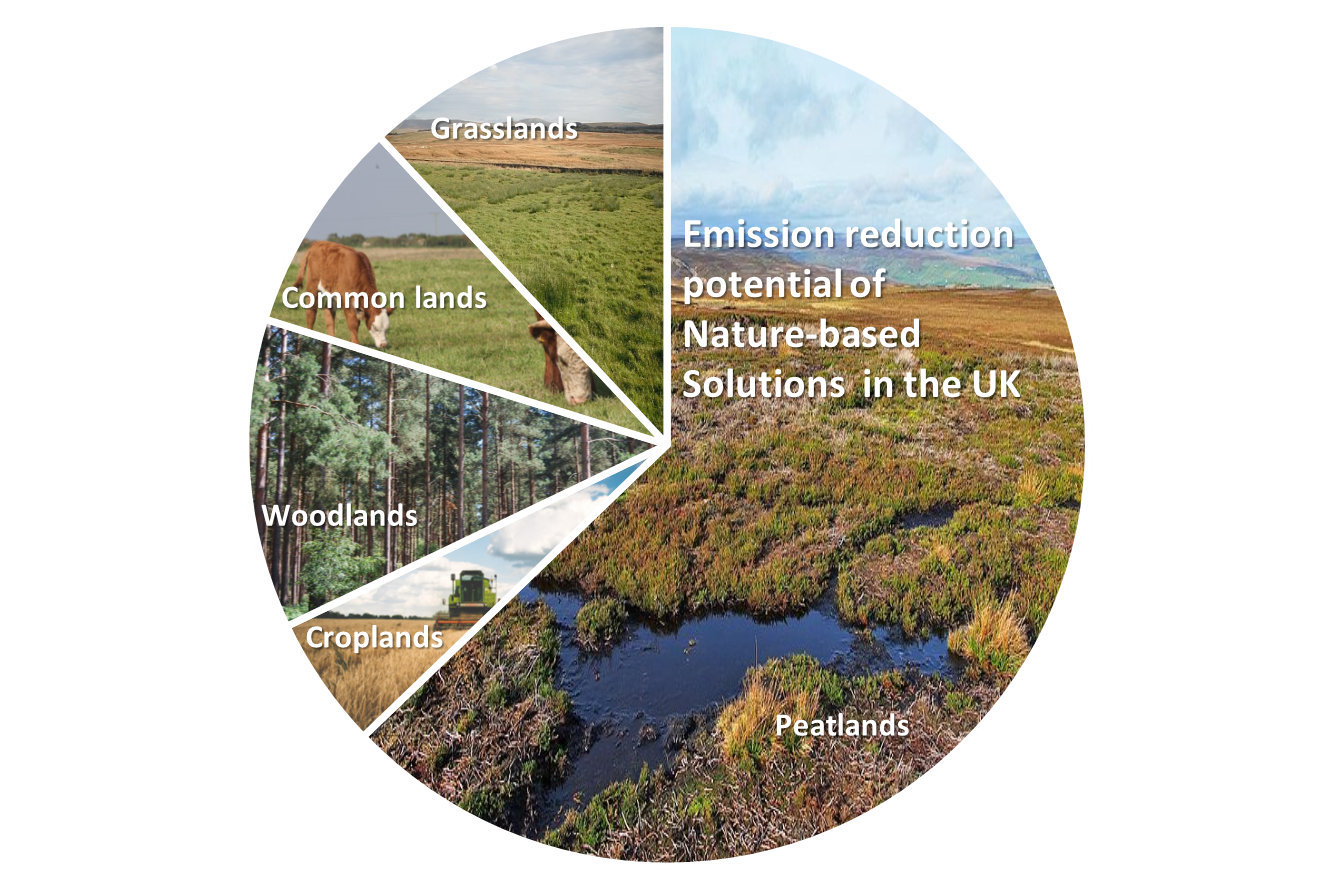

There is also scope for the UK use its presidency of COP26 to promote effective and fair NbS across the globe. In this context, the briefing recommends that the UK promotes a broad range of NbS that goes beyond the present emphasis on tree planting. In fact, while the authors acknowledge that commercial forestry plantations can be necessary to meet societal demand for timber and wood pulp, they caution that the promotion of afforestation with non-native species can have detrimental effects on biodiversity, for example when they replace species-rich grassland ecosystems. They can also lead to the release of carbon into the atmosphere, if carbon-rich habitats such as peatland are replaced by the shallower soils of plantations.

The authors warn, too, that NbS can never be a substitute to the urgent and thorough decarbonisation of the economy. NbS can only contribute to meeting international targets of climate change mitigation if they act as a complement to the main task of transitioning away from fossil fuels. There is a risk that NbS could be used to justify ‘business as usual’, by conveying the illusion that emissions are being compensated for by deploying NbS.

NbS are most effective when they are strategically deployed to minimise trade-offs and deliver simultaneous wins. For example, restoring upland peat in the UK can help to protect communities from flooding and soil erosion while also storing carbon, providing recreational space and natural habitat for wildlife with negligible loss of agricultural potential on the national scale. In contrast, replacing highly productive agricultural land with natural habitats could make the UK more dependent on food imports.

Also crucially, local communities must be involved in every stage of the planning and implementation processes. This is essential to ensure that local people do not overwhelmingly bear any costs associated with NbS, that they receive a just share of the benefits, and that they support the projects in the medium and long terms.

Prof Coomes “I am excited by the opportunities that COP26 provide to make the most of the potential of NbS to deliver climate change mitigation while benefitting biodiversity and livelihoods”.

Existing carbon stocks in the UK that should be managed, protected, and increased as NbS for climate change. Proportion of each NbS taken from WWF/RSPB 2020.